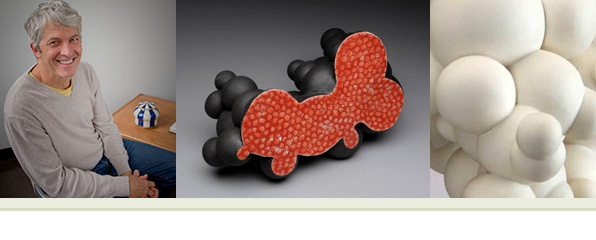

Jamie Walker is a Professor of Art at the University of Washington and was the recipient of the Distinguished Teaching Award in 2008. He was appointed Associate Director of the School of Art in 2011 and became Director in 2014. He studied at the University of Washington where he received a BA/History and a BFA/Ceramics before receiving his MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1983. His work has been featured in 24 one-person exhibitions and numerous group exhibitions throughout the U.S. Collections include the Seattle Art Museum, Henry Art Gallery, Racine Art Museum and the International Museum of Glass. Reviews of his work have appeared in Ceramics: Art and Perception, Sculpture, New Art Examiner, Ceramics Monthly and American Ceramics. In 2005 he was honored with a Flintridge Foundation Artist Grant and in 2010 completed a three-piece outdoor commission for Vulcan Inc., located at the Amazon headquarters in Seattle.

For more information: More Information

When you finished school what was most difficult for you?

Making a living and pursuing my passion in my studio while at the same time finding enough hours in the day to do both. Making an income and making work at the same time.

What where your goals when you finished school and have you achieved them?

I vastly exceeded my goals from when I graduated. When I got out of graduate school I moved from the East Coast to the West Coast where my goals were to set up a studio, make limited high-end production work, and participate in American Craft Council fairs. I got to California and within two weeks that goal changed because I met many people who were doing exactly that and they were making a really good living but their work didn’t mean that much to them anymore. I decided that I just wanted to make the work that I wanted to make. My immediate goal was to have representation in commercial galleries. I found a studio within a week of moving to California and I got a job doing construction work and started making my own work. I had some lucky breaks and I started joining commercial galleries eight months after I graduated and I got a lot of exposure from the first big show I was in. I was able to quit my construction job after about a year and just worked as an artist full time. It was my dream to be a self-employed artist and I did that for five years. That was wonderful and I was pretty happy with the work I was making but it is a pretty solitary life. On the financial end of things it was hit and miss whether a gallery would pay me on time or at all. I began to get more involved in teaching at the local community level and it just grew. After about five years I decided to apply for some regular teaching positions. I started off as a visiting artist for one spring at Ohio State and then I got a part-time position in San Diego, which I was delighted to get. After about a year I was offered a tenure-track job at two really good schools. I took the job at the University of Washington. When I sat down in my mew office for the first time, I totally freaked out and froze because I wasn’t even thinking about applying for this job, I didn’t think I would really be considered for it. A few people encouraged me to do it. As that process went on I was flown up here and did an interview. Although I thought that it had gone fairly well, I was shocked when Patti Warashina gave me a phone call and invited me to come up. I got here and called a friend, Michael Lamar, from graduate school and just confided my greatest fears of having this job. He was really great. He said ‘it’s our time, you’ve been out of time for five or six years, you deserve this type of job and don’t whine about it, just do a great job’. Again, never in my wildest dreams would I end up in a place like this where I started working with Patti Warashina and Bob Sperry, who was retiring. I was the new young kid on the block. A couple years later we hired Akio Takamori which was really amazing. Then Patti retired and we hired Doug Jeck. Even now I pinch myself that I actually was able to work with these people. So I’ve totally exceeded all my expectations.

You talked a little about commercial galleries. How do you know what galleries were right for you and how to approach them?

I went to graduate school at RISDI so I was really embedded in all things ceramics, living, breathing the dust and everything about it all the time. That was the 1980’s during this real expansion of ceramics nationwide with galleries in New York showing contemporary ceramics for the first time. They weren’t necessarily craft galleries; they were commercial art galleries. A gallery in Seattle had approached me while I was in graduate school and asked me to send some slides when I graduated. I did that, and, based on that work, they invited me to be in this big national ceramics exhibition. That was a fairly big deal. I did a little installation piece. The show got enough publicity that they extended it because it was a nice overview of contemporary ceramics in the United States. Another gallery owner in San Francisco saw the show and they contacted me about showing in their gallery. In retrospect, things fell my way a little bit with these opportunities. Being in the Bay Area was fantastic because they had this great legacy of ceramics starting in the late 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. More galleries in San Francisco showed clay than any other galleries in the states. When the opportunity came up I just tried to take advantage of it and max it out.

For ceramic artists starting out today are there privileges that may be present that were present before?

2008 really changed a lot of things when the recession hit. It’s still about the work. If you have really good work, and you’re not afraid of getting it out there so other people can see it, then the strongest work finds an audience. You can’t just bury yourself in a cave and expect people to discover you at that age. There are opportunities out there. You have to be smart about which ones to pursue. We’ve had a number of students come out of our program and they’ve done really well. They usually start out doing showing locally where our program has a strong reputation in the greater Seattle area in the commercial gallery world. There is no bias against students coming out of the UW ceramics program. Commercial galleries will go to the thesis shows and see the works and people got picked up from that. It happens every year or so for students like Alwyn O’Brien, George Rodriguez, or Jacob Foran and many others whose work was predominantly clay that was picked up by a gallery. Then they can expand upon that. Some of them have broadened their reach into other cities. The West Coast makes a lot of sense, especially California. Jacob had a recent show in Chicago. Los Angeles and San Francisco are both areas where a lot of our alumni’s end up and have been able to carve out careers there. The work first needs to be really really good and they have to be productive. What I meant by taking advantage of an opportunity is if someone’s interested in your work and they might say we’d like you to be in a group show in six months. Then you need to figure out how to get the best possible work you can into that show. If they offer a solo exhibition it’s the same thing. Those are the opportunities that you have to maximize because if you don’t it doesn’t make any sense for the gallery to establish a relationship with you. In terms of reaching goals, the caliber of students who we produced in the past decades here has been fantastic. I was in New York last month and one of our undergrad alumni, Shio Kusaka, had a show in Chelsea in a great gallery. I walked in there and it was this beautiful Chelsea gallery. The entire gallery was filled with this quasi installation of her pots all wheel thrown pots with very intelligent simple decorations on them. About 90% of the shows had sold for prices from $400 to $10,000. I had the biggest grin on my face realizing that pots were in this Chelsea gallery, people were buying them for great prices, she got a review in New Yorker magazine, and the fact that she learned to make pots in our program 10 years before. For her to get to that point it was always about the work. She always figures out a way to keep it going and she does it. She has started a family and she’s somehow been able to pull all this together and make it happen which is really fantastic. It’s much more challenging today than it was 10 years ago to make it; but the ones who do make it, their work is really good, they have a fantastic work ethic, they’re not jerks and they have a certain amount of business savvy or they know who to ask who would help them with that. If they get an opportunity they figure out a way to make it happen. Post interview update: Shio Kusaka was included in the 2014 Whitney Biennial.

Do you think your students have more of an advantage then other schools because of your location in a large city?

There’s probably an advantage over some schools, but I was back east over the summer and I was shocked how isolated Seattle is. It’s not like the East Coast where there is a much closer knit community and a lot of opportunities happen because you factor in students visiting different schools or seeing different shows. I went to New York specifically to see that Ken Price show and I found out that the Shio show was there. It was an added bonus. Then I was at Haystack teaching for a session and half my students were from New York and had seen the Price show. They didn’t know each other but they all had gone to the same show. That doesn’t happen in Seattle very often. There’s not that much going on. The biggest benefit is that we have a pretty strong reputation and if people come to town they will often visit the studio and specifically be interested in looking at the graduate students and seniors. We have many students who start off in clay and they migrate into some other materials, but that’s expected. It’s definitely an advantage for them to come out of this program. I think that for some of them it’s not a big enough area especially after the recession. A lot of exciting galleries closed and some dealers are a little bit more conservative in terms of taking chances to support young people.

How does living in Seattle benefit you personally as an artist?

It’s one of the most beautiful places in the world to live. I like being in an urban setting but I also get to enjoy the water and the mountains. The weather gets a little dreary at times but the last few months have been the greatest weather in Seattle’s history. At the same time it’s small enough where there aren’t millions of distractions so you actually can get work done here. My primary gallery is in Seattle, the Traver Gallery. I don’t produce as much work and I don’t show as much as I used to, which is fine. Living in LA or New York or a large urban center would be very distracting with too many other things going on. Here you can concentrate on your work. Because of the UW, the Cornish College of the Arts and people just moving to live in Seattle there’s a great arts community here. It’s relatively small but it’s fairly sophisticated. There’re some really great collectors and patrons of the arts here with an acceptance of ceramics and the museums. The Seattle Art Museum, Henry Art Gallery, Tacoma Art Museum, and the Bellevue Arts Museum, all have significant holdings in contemporary and historical ceramics. For me being here and having my position at the UW, I always thought this was the greatest job I could ever get and I still feel that way.

How do you keep a balance between making sure your present enough as a professor and working enough in your studio and having time for yourself a home?

I started here in 1989 and we had one child who was seven months old. We very quickly had two more kids. I was an assistant professor going up for tenure while the program was really undergoing this fairly dramatic generational shift. My wife was amazingly supportive in many ways. I’m not sure how much I helped sometimes at home, that whole period is a blur I think and I nearly had a heart attack. I want the teaching to be as exciting as my studio work and the only way that’s going to happen is having really interesting students. It seems like there’s a correlation between what you put into creating a dynamic atmosphere and the engagement you have with students. I think that’s why our program has been as strong as it has been because our faculty have always been willing to commit an inordinate amount of time and energy to it. The upside is you get really curious and motivated students so that you’re challenged and they keep you on your toes. At the same time, to have any level of respect with my students, my studio work has to maintain a certain level of relevance. At times that’s in some ways harder to maintain. Part of that is balancing the triad of a teaching career, studio, and family. I think my family got the short shrift for a while and at a certain point I woke up to the fact that they are way more important than my teaching or my studio. That’s when I reprioritized things so my family was first and then my teaching and then my studio. I love spending time in the studio and making work and know that I’ll always be able to do that. I have a studio at my house which has been great. It’s in a little building in the backyard so every night I go to my studio; sometimes after everyone has gone to bed. I’ll stay in there for an hour or three. Some nights I get dirty and make things while some nights I’m on e-mail or doing something else that’s more school or family related. But I’m in there almost every night. It’s where I work and so I feel like I’m always engaged with that even if I’m not actively making things. Balancing has always been really hard ,but now my new mantra is to just pick my moments. When NCECA was in Seattle in March of 2012 there were a lot of exhibition opportunities I really wanted to max out so I let other things slide to be able to do that. Then I had to recover a little bit and catch up with family and school. I started saying no to lots of things which I had been doing for a number of years. I still say yes to some small opportunities like this group show in Italy that is kind of like a dream come true. That’s my focus right now, just to get the work done for the show in Italy. I’m just trying to be realistic about which moments I have time to pursue. I’ve begun drawing more partially because of it’s immediacy when compared with the cycle of ceramics. I’m doing more administrative work and will start doing a lot more administrative work in less than a year so I’m very leery about how that balance will be shifted. I will back out of teaching to do the administrative work. What I’m trying to figure out is a way of setting aside a couple hours a night. That’s my time for studio. I won’t take my laptop in my studio anymore because of the endless nature of the administration. For me to be effective in my studio is to really focus. Today and tomorrow are supposed to be studio days, but the morning got out of control and I had this meeting with you and I have a meeting after this and then I have another meeting after that one. My family is gone for two days and so it’s looking like maybe I’ll be getting in the studio at six or seven tonight. At that point I’ll be able to fully focus tonight and all day tomorrow. Fortunately I’m way more efficient than I used to be. That’s something that’s really different from my early days. When I was a self-employed artist all I did was wake up in the morning and decide what I wanted to make. I could sit in my studio and sketch and think and ponder the universe and decide whether something should be red or yellow. I could spend eight hours thinking about that but I can’t do that anymore. A lot of the thinking that I did back then was really important at that time. Now I can make those decisions a lot faster. Partially, it’s practical because I need to but also I have a lot more confidence in the choices I’m making. I actually work differently now as an artist then I did 20 or 25 years ago. Part of that fortunately fits into having less time to do it.

Do you think that success or failure contributed to how your work has changed?

There is the period I can recall that I thought I would have a heart attack. I was making a lot of work. I would have two one person exhibitions a year and a bunch of group shows. It was always new work in every show. I was making stuff and shipping stuff and doing all that at a crazy pace. Then I started teaching full time while still trying to maintain that pace. A lot of the work I made was fairly complex and large-scale, so I’d be working at a piece for a couple weeks. That was getting really complicated. One of the problems was some of the work wasn’t very good because it was rushed and I didn’t have enough time to think about what I was doing. Fortunately I was able to go away for a quarter and teach in Italy. When I was there I tried to look at my life. I loved being in Italy teaching and being with my family. I had time to think about what I was doing and I had time to think about what I was doing back home in my studio because I wasn’t working in clay. I was making this stuff that was exhausting to complete. It wasn’t that much fun anymore. I was doing it because I was supposed to be doing it. So, I came up with this mantra of dealing with my own reality and my reality was I had one or two hours a night in my studio and it’s ridiculous to be working on pieces that take weeks to build. I decided to make small pieces where I could actually get something accomplished each night. I talked to my main gallery dealer in Seattle because I had postponed an exhibition twice and they weren’t very happy about that. They told me I didn’t have to have these grand exhibition extravaganzas anymore so I thought about working at a smaller scale. I got back to Seattle and began to make these smaller, more manageable pieces. The show was scheduled and it grew from there. With the scale shift I was able to get things done and I felt so much better about it. I’d work every night and after two hours and I said ‘wow, I got this done’. I would work the next day on another one and get it done and I would think ‘that’s great’. That was a major shift in my thinking. If I’m working on a more ambitious piece then I know that I just have to carve out the time so I can get on with it and do it. That’s my primary thing for that day or that week or that month. I’m being smarter about the time required and what’s required with the rest of my life to get this done so that I can insure that it’s an interesting and positive experience for me and for the work. That’s again just gained from experience. I feel like in the past couple years I’ve been able to do that much better. Recently I also did this large project in downtown Seattle, an outdoor commission made of aluminum, which I don’t usually work with. It was a design build process with maquettes made of clay. The process of having other people make it while I would just go in a couple days a week that fit my schedule great. But it was weird not being able to make my own work. After a couple months of that I got back to the studio and started making some pieces based on that experience. Realizing the reality of my day and that balance between teaching and family and studio and also just personal health and other things is important. I’m okay with less production. I’m hoping that the work that I do produce is not quite a shotgun method of making lots of things and hoping something comes out. It’s more focused now.

How do you stay connected to your peers in the community of ceramic artists or do you stay connected with other artists?

In Seattle were really removed from the national community so I go to NCECA once every three years. I go there mostly to see old friends, some of whom I am in touch with regularly and some I’m not. It also gives me a chance to see what other younger people are doing who I might not know. I no longer subscribe to any ceramics magazines, so I feel a little out of touch with the greater ceramics world. I think that with the way that my career has gone and the way our program here has gone that most of my peers consider themselves artists instead of potters or ceramic artists. On the local level I think I’m very in touch with the local clay community and arts community. That feeds a lot although it’s exhausting sometimes. I didn’t go to Patti Warashina’s opening last night because I went to another private opening a couple weeks ago and I’m going to something else for her in October. She’s not going to miss me and I don’t need to see all those people. Occasionally the beauty of e-mail is someone like Julia Galloway and I can have an exchange. Some of those connections are people who you are not best buddies with but you know each other’s work and you have this mutual respect so it’s easy to have a conversation. There are people that I really do keep up with, people who have active websites or send out quarterly mail or engage with my students. We have our students here do research projects. Last fall I came up with a list of mostly international artist that I didn’t already know. I asked Akio and Patti who are people you’ve heard of internationally and the students had to look through and pick someone. The students would Skype these people in Japan, Canada, and Sweden so they would give these little 15 minute reports. They were fantastic and it’s like meeting all these people. One guy they interviewed live during their presentation and he was in his studio showing stuff with a translator there to translate his Japanese. That is something available to us today that’s really great. Most of it comes from seeing the work, so I try to see as many exhibitions as possible.

What in your opinion is the greatest challenge facing students about to enter the field as professionals?

As professionals, on the bright side there’s always room for really great handmade work whether it’s pots, sculptures or whatever. If it’s good and if you’re smart you can find a market for it. In some ways there is increased competition and the reality of the cost of living. When you look at buying a nice handmade cup you’re looking at $40-$90 and there are a lot of people in the world who have no idea why they should spend that money when they can go to IKEA and buy this very cool, maybe even hip, production cup for five dollars. That challenge to market yourself is greater as the quality and design sensibility of industrial products just keeps getting better. I have watched the career of Ayumi Horie, who is an alumnus from here, with great interest since she sells the majority of her work off her website. She’s very smart, makes fantastic work, has great business savvy, and has great friends who give her good advice as she works her tail off and keeps things moving along with a buzz around her work that keeps evolving. I was talking with one of my colleagues the other day about this. For a lot of us who got to the position where we are, the one thing we have in common is working insanely hard. Again, our top students seem to find a way to make things work. When I started out at local craft fairs and storefronts they would support my studio. That staircase starting off as an amateur and working my way up seemed to be more solid than it is now. The other thing is the rising cost of living in an urban area and supporting a studio habit. I’m not sure it’s any harder today to make it than it was 30 years ago, but it is definitely different. A lot of it in the pottery world is the industrialized product is way better than it was back then which wiped out that whole middle zone for production pottery. On the art end of things ceramics isn’t segregated anymore so you can show in galleries in Chelsea or galleries that show sculpture and painting and photography. It doesn’t really matter. It’s kind of quant the way we have cup shows and teapot shows. When I got out of school I made cups and I was in six or seven shows in one year and every single cup I shipped out I sold. They went all over the country and they were just little cup shows. In the long run it helped my career a ton because that little slice of people knew my work. As my work grew away from those things, those people have followed a little bit. We still have that in the ceramics world but I don’t think as much as it used to be. I guess I’m conflicted, I’m not sure if that’s a good thing or a bad thing.

My last question is do you have some parting words or advice to give to emerging artists?

For me the most important thing that I discovered, literally a month after graduate school, is to make what you really need to make as well as possible and try to share with others. If you find an audience more power to you but be true to yourself first. Remember that things don’t always work out. My career has gone up and down. In the early days I had shows sell out on the opening night, 60 pieces, and another show a year later I sold 1 piece out of 60 pieces. The work in the second show was way better in my opinion. I think it’s really important to be true to yourself. If you look at most successful artists out there in the real world, they didn’t follow a certain path, they all created their own thing. In a funny way that’s what a lot of the world is interested in, that kind of individuality. If you’re going to spend all this time making this by hand then really take advantage of it. When I look all our alumni who’ve done really well they’ve done it their own way. If you look at their work it doesn’t look like mine or Doug’s or Akio’s. We might’ve influenced them in some ways but it is their vision that made them succeed.