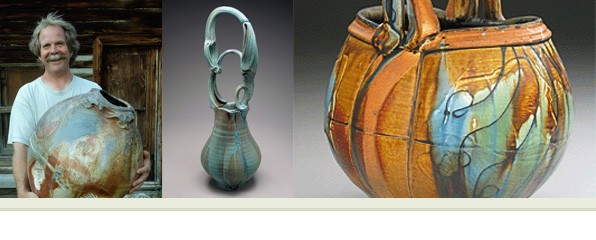

Josh DeWeese is a ceramic living in Bozeman Montana. DeWeese received his BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute and his MFA from the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University. He has received several awards for his work, including a Montana State Arts Council Individual Artist Fellowship. DeWeese has exhibited and taught workshops internationally and his work is included in public and private collections around the world. For many years DeWeese was the Director of the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Helena Montana.

What was most difficult for you when you finished school?

I think the most difficult thing was just leaving the community of the school and the comfort of that studio environment where it feels like you’ve got a whole camaraderie of people and all of a sudden you’re on your own. I think that’s a factor, and also just making sure you have a place to work somewhere. Those were the most terrifying things to me, but I was really determined to keep my hands in it one way or another so I was able to do that.

How did you go about doing that?

Well, fellow students at the Art Institute in Kansas City told me about the art center in Mendocino, California. It was very accessible to go there. I basically just said “I want to go” and I was able to. I didn’t have to apply to it or anything back in the old days. I enrolled in a program at the art center there called the Regional Occupational Program which was a California state funded job training program that had a two-year program to teach people about making pottery. So I enrolled in that. It was $30 a month for the studio fee, which I thought I could manage, and then we also had to pay for firings.

Were you there at the same time as Robbie Lobell?

I was. It was exactly the same program, the same class and everything. It was pretty amazing. Maybe Robbie talked about the experience as well. It was really good because it gave me a place to work, which I was eternally grateful for, but it also was a community which was probably just as important. You can have a place to work in your garage, but it’s that community of people, I think that you need to get into that’s really important. That said, some of my good friends from school in Kansas City moved out there at the same time. We went out there together, but we kind of ended up there about the same time so we had a shared past experience that made us superior to everybody else [laughs]. Looking back on it, I had just graduated from the Kansas City Art Institute. It was a really good school, and I thought that I was pretty good. My head was pretty swollen. I thought I was one of the greatest things in the world. So we moved into the studio with this great group of people, but really inexperienced, too, so we had the run-of-the-mill with it in a lot of ways, in a pretty good way. I think it was pretty positive for everybody; even the people that we were being arrogant toward. Being recent art graduates, I think that our egos were a little bit too swollen. That’s okay, though, it all worked out fine and I think that we did bring a buzz. We had a great time and we worked all the time. It was a great way to keep working. I worked at a restaurant a few nights a week and made pots. I lived like that for a couple years and didn’t look past tomorrow. It was kind of nice, but I knew that I didn’t want to do that forever. It was fairly short-lived.

Did you then start looking for galleries or just places to sell your work and how did you know what places were right for you?

I didn’t even think about it that way at all. We did pottery studio sales. It was that period of time where I entered some shows but we made stuff and then we would put a big sign on Main Street to direct people down there to sell pots. It was really down and dirty at the art Center in particular. I always enjoyed that moment where you could do that at that time right when you got out of school. You can do things like that and I encourage people to do that all the time. If you’re making, things usually get better. Not always, but that kind of peer making is usually beneficial for people at that stage. I didn’t even think about gallery representation and in Mendocino there were a lot of different shops but I could never really see my stuff fitting in there. I couldn’t visualize it there at all, so I didn’t really pursue that.

How long did you stay in Mendocino?

About 3 1/2 years. There was a 2 year program that I was in. Two friends who were in that program and I rented a little space that was just down the block from the art center. It turned out it was about the same distance to the kiln shed as it was from the studio at the art center. We rented this place and developed it into a little studio. We had a gallery there with a little showroom and it was right on the traffic way from the Art Center down to the main drag. We didn’t get a ton of traffic because we didn’t market it that well, but we got some. That was the first time that I really had an opportunity to have a studio and a showroom with it. I had seen that example enough that I thought it was a smart way to go. If you can capture your market that way it’s a good thing to do. Then we worked out a deal with the guy at the arts center at the time that we could fire the kilns there at cost basically. He liked having the activity going on and I think it was sort of a win-win situation. I really loved being down there but I didn’t ever feel like it was a long-term thing. It felt temporary, like doing time somewhere for a while which I cherished but I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life there. I did that for a couple years when a friend there from France was going back to visit his parents and said “hey you should come”. There was an opportunity to go traveling in Europe that lasted for about six weeks. Then I went from there to the Archie Bray for the summer because I got a grant to go up there for a summer. That was a lucky break. Kurt Weiser was the director then and he said they had some funding from the NEA and had five $2000 summer grants. I had applied to go up and work there that winter in January and was lined up to go. Then I got this opportunity to go Europe and I called Kurt and said ‘I’m going to go to Europe for a couple months.’ He said ‘that sounds like a good idea. I’d go too if I had the chance.’ Then he told me about these grant opportunities they just found out about and said ‘you should apply for one of those’ so I did and I got one of them. When I came back from my trip I just moved right up there. I was there for a long time. It fell right into place. I went there as a resident for the summer and didn’t really think about staying for a lot longer. Then when fall came around I thought I would stay on but I didn’t know what I was going to do. I had a job at Bert and Ernie’s in Helena; the old version before it moved into the big new one right next to the general Mercantile and it was a hole in the wall sandwich shop. I made sandwiches as a winter resident. It’s so different, like night and day from what it is now. One day I was walking through the kiln room and Kurt said ‘hey do you want a job’ and I said ‘well what do you want me to take the trash out?’ He said ‘well I’m leaving in January and they need somebody to hold down the fort over the winter until somebody can come in the spring’ and I said ‘you want me to do that?’ I was in a state of shock. I was the acting director for six months and it was total euphoria. I was so excited. I was just in this total zone of utter bliss and terror all at the same time. I was there for the summer and went to grad school that fall. I came back both summers I was in graduate school. Then I got out of graduate school I didn’t know what to do again, I was in the same boat. I went to Vermont and I came back to Montana for a little while. I did a workshop in Mendocino then drove all the way out to Haystack, Maine. Rosie and I had met at the Archie Bray earlier at the time I was in school at Alfred and she went to school in Kansas City. So that summer we went up and wear monitors for Jeff Oestriech at Haystack for three weeks. Then coming back a friend of mine, Henry Tanaka’ who I was in school with had a job with the Vermont state craft center in Middlebury. I went to work there. I had a studio space and taught children’s classes there which was an interesting experience. That was terrifying too. I had this tile project for kids the first morning and within five minutes this one little girl was like “I’m done!” and I was like ‘what! Do it again’ I don’t think I was really good at it. I got to see Bread and Puppet Theater which was really great theater group in northern Vermont. Then I came back out here that winter and taught 2D design classes here at MSU. Rick Pope was teaching here and Rick hooked me up as an adjunct teacher so that I could fire here. Anyway I couldn’t count on keeping my hands in it. I didn’t know what I was going to do so I thought maybe I’d build a kiln at my parents place and set up a studio at my dad’s place since he had just passed away a couple years before. I was in that postgraduate school limbo. I was still working and making stuff but I didn’t really know what I was going to do at all. Then I got a call from Carroll Rorbauch one day and she said to come do this workshop for her at Arroumont. It was the first utilitarian clay conference that they did so I said ‘Yeah, I’ll do it!’ She just couldn’t do it and said everything was going wrong where she was and that she was going to resign. She asked me to do this thing and tells me she’s going to resign and I’m thinking that’s terrible, I really want your job. Then it all just kind of fell right into place because I had been there as the acting director before so they said get DeWeese up here he’ll do it. I went up there and officially applied for the job that winter. I got hired and was there at the Archie Bray for 15 years. I’ve really enjoyed a privileged position in this field because my parents knew a lot of people like David Shanner, Ken Fergason, Rudy Autio, everyone who was on the board at Archie Bray. They all knew me before I knew them. They thought I would be a good fit for the place and so they just plugged me right in there. There was hardly any question about it. I couldn’t say no and I wouldn’t have wanted to say no anyway. It’s kind of the story my life. That’s what you have to do in this field; just be born into the right family, work hard, and it will all work out.

How did you decide on clay as your media?

I tried desperately not to go into art. I didn’t want to have anything to do with it because it had been so powerful during my childhood. I didn’t want to be like that. I was rebelling in a pathetic way and I thought I could do pottery because there was a practicality to it. I’d had ceramics in high school. I enjoyed it but I didn’t excel at it. When I finally pulled my head out of my behind and accepted that art wasn’t a smart thing to do, it just was, and there was no other choice that felt right. I’d tried to study architecture a little bit and got so perplexed so quickly that I ran back to the art building with the idea that I could take ceramics. I really thought I would take ceramics because pottery has this practicality to it that I was really attracted to that idea. It wasn’t a highfalutin kind of art thing and the people who were teaching here were a whole bunch of Kansas City Art Institute alumni like Michael Peed and John Buck. Two of the graduate students at the time, Mike Murer and Jim O’Connell, had also gone to school there. As I was getting interested they said you should try to go to Kansas for school. When I floated that to my parents they were like ‘oh, okay.’ They were very supportive. My dad had a scholarship to the Kansas City Art Institute when he was a kid. It was like a $75 scholarship and he wanted to know if he could apply that toward mine because he never used it. It was kind of a joke. My parents had five kids. My four siblings were all a lot older than I was so by the time I came along they were pretty well out of the nest and my parents were broken in already. I got spoiled rotten. Well not rotten, but I was pretty much a spoiled brat growing up. I got everything I wanted. I didn’t have to compete with my siblings and I had really good friends growing up. My parents were weird, that’s the way I looked at them. The environment was weird. The parties were unbelievable. The best parties imaginable all happened out of my parent’s house. All the art students would be out there all the time late in the 60s going into the 70s and it was wild and crazy. I look back and think ‘god that was so amazing’ but at that point I wasn’t that enthralled with it. Looking back on it my appreciation for them and their work and just their lives really expanded the older I got. I’m still amazed about what they were able to do here. Their work is really inspiring to me. The other thing that was always really inspiring was their interest in community was really important but I took it for granted. I can see how important it is now. They were very open and people could stop by there any moment. They would be welcomed with a hot cup of coffee or a beer or scotch and then just tell me what they’re doing. They were inherently curious about what somebody else’s experience was and wanting to know about that sincerely. It wasn’t a façade at all. That’s really inspiring to me. I think about my siblings like my sister who has been able to carry on that spirit better than I have a lot of times. We all do what we can do.

So you grew up in Montana and you ended up coming back here. How important is location for you as an artist and how does place play into your work or does it at all?

My experience has been so based around the Archie Bray experience. I could’ve ended up going somewhere else. I think that could have happened. If the job at the Bray had not have opened up I could’ve very easily ended up going somewhere else. This place has always felt like home even when I went to school in Kansas City and New York and spent time in California. Coming back here always strongly felt like home because of my family was still being here. Montana always felt like home but Bozeman didn’t feel like home for a long time. Sometimes even now I question it. I grew up in Bozeman but it has changed so much. It’s changed dramatically from when I was a kid and when I was in high school. It feels like it’s been invaded, there are so many new people here and the social climate is different. In Helena, when I first went there, I didn’t like it but I just grew to really love it because of the community mostly. There was such an intimate supportive arts community there that I remember from when I was a kid here, in Bozeman, but frankly I haven’t been able to find it again. The school’s rich but there’s not as much connection back out with the community. It’s mostly my experience and I don’t think it’s anybody’s fault in particular. That’s how you choose to get involved with things. Place is really important, particularly with the idea of establishing a studio and a pottery. I am interested in local material development but also my studio environment. I want a studio to be like a long-term home for the long-term development of a piece of sculpture. In a way, kind of like the way Archie Bray was. How you design a place the gardens and a studio and the kilns work within that environment building that out into the community. I feel like that takes a lifetime. I think place is really important for people to think about.

What made you decide to come here in the end?

When we were at the Archie Bray we got a house to live in there as part of the package. We thought that it would be smart to buy something. Rosie’s from Billings and she didn’t want to move back to Billings and I certainly didn’t want to move back to Billings. Bozeman, was a smart choice because the University seemed like a pretty good possibility in the future and because my mother and my sister were here. It was a logical place to buy some investment property. That’s what we did. We bought a place and rented it out after fixing it up. We still have that place. Now we have a couple other places too which is crazy but we do. It’s like Monopoly. We bought the first place because the place next to it was abandoned thinking it would be great if we could get that place. Then we found out who owned it, made him an offer, and he went for it. So we got that place too and we’ve built our house there. Just recently a neighbor on the other side of us passed away and his place came on the market and it was so close we sort of bit the bullet and got that one too. We have two rentals and the house now all with the idea that property is a good long-term investment and then we can also control our borders a little bit. When I left the Bray, Rick Pope was still teaching here. As soon as I said I was leaving the Bray he said okay I’m retiring and you’re going to take my job. I’m serious, that sort of the story of my life; Sort of laid out in front of me. That fall he went on sabbatical and I was a guest teacher here. I applied for the job five years ago and I’m still here. It’s fantastic. It’s one of the greatest things in the world. Really challenging but endlessly entertaining. I’m really in the middle of deciding if it’s a smart move or if it’s the right move. I think it is for me. I don’t think that I’ve ever really been a studio potter. I just don’t think I have that kind of ability as much as I’ve wanted that. I always had this feeling I could go either way but I don’t think that’s true. I think if you want to be a studio potter you need to really start with that intention. It takes a long time but you can do it if you live within your means, you build it slowly, and you build your community. I think it takes a real commitment and you have to practice that lifestyle. I’ve realized that in the last few years because I think it would be impossible for me to step out of my world here and do something like that. I think I would fail even though I really would love to have more time to make pots. It’s not what I do. I don’t know what the best answer is for people. I think if you really love teaching and that feeds you then it’s good to go after that. It’s still a good option I think for some people but certainly not the only option. I think you can do better financially outside of it if your entrepreneurial and you’re creative that way. Academia is changing and the pension plan accounts people had are not seen anymore. I don’t know where they are. Wouldn’t trade it for anything either. I feel really lucky in the range of people you have contact with. The students are always new. It’s the way residents were. We don’t have kids so I think that makes those students much more critical; that young energy all the time.

How does teaching here at MSU differ from your job as the director at the Bray?

It’s completely different. At the Bray everybody there was fully committed to the idea of a life in clay or in the arts on a really serious level. You took that for granted while you’re there. Here, at the university, that’s clearly not the case. The other big factor is the investment that people are making with school these days is terrifying. It makes me question that a lot. Are people really getting their money’s worth? I don’t know. I worry a lot about how much debt people are in when they go to school and how unconcerned they are until they see the final bill. Even my personal experience with it; coming to the realization of what that investment really is for people. The challenge of teaching is really another thing. I find it tremendously challenging. Some days I think I’m really good at it and some days I think I’ve done terrible. I would bet that’s how most people feel trying to deal with it because sometimes it’s the best thing in the world and sometimes it’s really hard. I think also at the Bray the whole time I was there I was infatuated with the idea of what the place is and being really inspired by that, that fed me a lot. It was a hard job and it didn’t pay very well and was 24/7 but I didn’t care. There was a lot of growth while I was there and I guess that’s always good theoretically, although I question that sometimes too. I was euphoric about the history of the place and to be a part of it. It was really inspiring and feeding back to my family and my teachers it couldn’t be any better. I was really inspired by that. I could stay up until three in the morning and work and get up and do all this stuff and still be chipper about it. I don’t feel like that here as much. I’m still excited about it and I’m excited about the students and the potential but it’s also a much bigger machine and there’s a certain kind of hard reality to that. There’s only so much that’s going to happen realistically. We have to keep that in mind all the time and there’s a frustration with that. There so much you have to do to get things happening. I’m not too convinced I want to devote my life to doing that. I already have some other things I want to do.

How do you stay connected with the greater ceramics community and do you stay connected with other Artists?

Connection with other artists is mostly through the University with my colleagues. That’s clearly the biggest thing. Also, staying involved with the Bray helps quite a bit. I teach workshops because I get to meet a lot of people and that kind of gives me a little more exposure. I make sure I got to NCECA and I believe in that. It’s a good thing to be doing. I’ve also been doing this exchange program with a school in Korea too. I’ve been able to keep my contacts over there that were developed from the Archie Bray residencies. There are a couple of pivotal people who are really hot and very good and have been very successful in their careers. It’s been fun to watch them and live vicariously through other people that way. Most of it all stems from the years at the Archie Bray. All these contacts are phenomenal and we stay in touch. That’s the nice thing about NCECA, even if it’s a short check-in with people you get to see what people are doing and maintain that contact. I think the other thing, too, is just being continually amazed by what is happening in the field now. I watch everybody now and see how people have gotten so good. It’s really phenomenal, pretty exciting.

Do you think there are certain advantages or disadvantages facing students or emerging artists?

Yes, I can see it both ways. It feels like the emphasis on the level of professionalism is much higher than it was when I was coming up through the ranks. It’s amazing how people are able to present themselves today. It’s probably good but also it sometimes feels like it’s the cart before the horse. People put all their energy into that more than the work itself. It looks good on one level but it’s sort of a short-term outlook, justifiably. It’s interesting watching the residents at the Bray right now with the level of support that they’re getting which is still not very much but it’s enough to kind of make it possible for them to really have a go at being independent. That feels pretty new and I think that that’s a shift from before. It’s not all about getting a teaching job at all anymore. That’s maybe one option for people but now people are choosing to market themselves and think about different creative endeavors. They’re trying to support themselves and it seems like there are more possibilities. Whether or not those possibilities are truly viable remains to be seen. If people can kind of carve out something that can give them time to develop and invest in the long-term future as a studio artist, it feels it’s a lot more attainable. I don’t know if that’s true. I don’t know if it is attainable but feel that a lot more people will feel it’s attainable. The level of competition is ferocious, too. There’s a simultaneous level of competition and sense of greater community so there’s a positive side of that too. I don’t think its any easier and I don’t think it’s any harder. I think it still has to do with persistence and really persevering. Perseverance wins out in the long run all the time because, especially early in your life, it’s easy for people to easily walk away from it unless they really want to make it happen. It’s challenging for everybody in one way or another. There’s no one way to do it, also, which is great and terrible. We want a handbook…Oh wait, that’s what we’re doing right now!

I want to ask you about your own work and what influences you more success or failure?

Oh God! (laughs) The correct answer would be failure of course. But I hate failure, so I think that it is honestly a little bit of both. I don’t like a lot of failure I just don’t feel like I have time for that, it’s terrible that way. At the same time one of the worst things is a lot of success. Realistically I would never want to fail but I think that failure is way more important. It depends on what kind of failure it is too. “Ah-ha” moments can happen both ways. I don’t think I do very well with a lot of failure it shuts me down too much. I’m inspired if things work out then I could build on them. That said if there is too much it gets stale. It’s sort of like a quick death or a long slow death which is a bit cynical. I have a friend who teaches here in the chemistry department who was talking about how you never know where those moments of inspiration are going to come from because we want successful answers. We don’t want the failure but the failures that happen are usually where the answers are. I know that, logically I know that, but living that way is hard. I think it needs to be a little bit of both to make me happy. I don’t like to fail very much but I recognize that it’s important, too.

What do you think is the greatest challenge facing emergent artists today?

Money. The financial reality is really right up there at the top, there’s no doubt about it. It’s a combination of that and wanting instant gratification, too. It’s really hard. I don’t blame anybody for wanting that at all. People sort of set themselves up for hard lessons and that happens a lot. The challenge of understanding a long-term investment with this way of life is hard for people to grasp. I had a good friend who told me when I was a youngster the less you need to be happy the better. It’s true’ we all know that’s true, but that thing about living within your means is really a challenge. That and really trying to carve out a community becomes so important. Find the right place that will challenge you and keep you growing because sometimes it isn’t enough to just get a place to work somewhere if it’s a shitty place to work. I think that if there’s a will, there’s a way. I always say that and it feels like a copout but it’s really true! I think the people who really try hard and who show up and work hard and always say yeah I can do that. That always leads to more things for people. Recognizing that for younger people is a real challenge. I know everybody’s different but when you work with a group of people and there are some people who are always there and always wanting to be a part of things and then that compared with people who are sort of holding back for better opportunities which you can understand on the one hand but at the same time they are missing out. I think you have to have faith that if you are generous and go after it that all will fall into place. But money, that’s the biggest one.

How do you strive to achieve balance in your life and how has that changed from the time when you were a director to now when you’re an instructor?

Can I just flat out say that I’m not very good at it? I would say that right off the bat. My partner Rosie helps me with that by asking that we take time just to be. The reason I say that I am never very good at it is I always want to commit to opportunities whether they are teaching opportunities or workshops or shows. I haven’t gotten very good at saying no to those things so the deadlines drive that a lot as they do for everybody I think. Striving for balance comes with age and realizing that you can’t do everything. You really do have to say ‘no’ to some things and then identify the things that are going to be the most meaningful and put your energy into those. Again I can say that logically but the difference between logic and actual practice is I don’t feel like that’s actually good yet. I often get asked ‘how is it compared to Archie Bray’ and it feels about the same in a lot of ways except that I’m older and don’t have the same amount of energy as I used to. I feel it physically that I just don’t want to race the whole time and so I make decisions about deciding not to do some things. Balance really has to do with realizing your limitations and trying to make smart choices about things. I don’t think I can say much more than that. That’s the way I was at Archie Bray, I wouldn’t say no to anything and it usually got me in trouble but I was able to kind of make it work. No kids is another thing. I have a spouse and I have my family. My sister is here, but I don’t have children. I don’t know how people do it. It’s amazing to watch how they juggle. I think exercise, too. I’ve come to understand the importance of daily exercise and think its part of that balancing act too. Definitely highly recommended.

Is your balance at all different based on the season?

Definitely. One of the great benefits of academia is the summer. Even if you’re teaching a little bit in the summer it’s a totally different feeling. We live for the summer. There’s no doubt about it, it’s a great thing. You can get a lot more work made during the summer but I usually have a lot of things going on, whether it’s teaching here or a workshop. That’s consuming enough and there’re tons to do that needs to happen during the summer let alone your own place. At the Bray, the summer was out of control. That’s when you really were racing while here it slows down quite a bit in the summer. The big thing on the horizon here is we have this thing called sabbatical and I’ve yet to experience that reality but I’m going to go after it pretty hard as soon as I can. The older I get the more I understand the need for balance and that reality, but I still don’t think I’m very good at it. I don’t know that I ever will be. I want to take some real vacations. That’s becoming more desirable. I never thought about it that much before but I would love to do that now at some point. Just travel and not have to go teach somewhere. Just do it for joy. It’s a lot of work. These days I think everybody feels the same way. You need to peddle pretty fast to keep up these computers. It’s so great to me there’s so much going on but you can’t complain to anybody because everybody’s too busy all the time.

You have any parting words or other advice for emerging artists?

Showing up is really important. Also, I saw a thing recently that was really good. A woman did a presentation about gratitude. That thing about seeing the glass half-empty or half-full and counting your blessings. That’s really important for people to do. There is a video of David Shaner doing a talk up in Banff. It’s this lousy old videotape. Just listening to him talk was inspiring and he kept coming back to this line that you just got to have the right attitude and there is something about that ultimately it’s the key. I feel you could always see things from both ways and if you can see the positive side of things as much or more that carries you farther. Attitude has so much to do with it. Trying to see the upside of it because there’s always an upside and there’s always a downside but just put your focus on the upside. None of that’s easy. I think empathy is so critical to our well-being. Trying to get outside of yourself and see from somebody else’s shoes. We’re so lucky in so many ways and it’s so challenging in so many ways. Focus on the good parts as much as you can. People like happy people they really do. A smile gets you a long ways.