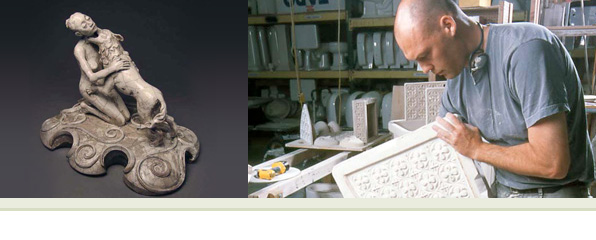

Justin Novak is currently the Assistant Professor of Ceramics at Emily Carr College in VanCouver, Canada. He was an invited artist-in-residence at the International Ceramic Center in Skaelskor, Denmark and at the Watershed Center. Novak has won several awards, among them an Oregon Arts Commission Visual Arts Fellowship and a John Michael Kohler Arts Center residency award. His raku-fired expressive figurative sculpture navigates a fine line the between the tasteful and the grotesque, while subverting the historical genre of the figurine, e.g. with his ‘disfigurine’ series, in which physical wounds such as bruises and lacerations serve as metaphors for injury to self-esteem and other psychological harm.

What advice would you give a young artist pertaining to the dream of being able to just make, but the reality of having a job that pays the bills?

Everyone has the desire to make a living doing something they find to be pleasant and interesting; that is not unique to artists. People that have a true passion, whether they’re amateurs or professionals, whether they’re making an income from it or not–they carve out time for that passion. It’s the litmus test, isn’t it?

I don’t know that I would necessarily recommend this widely, but in the period that followed my undergraduate schooling, and again immediately after grad school, I pared down living expenses to a very spare lifestyle in order to pursue my practice. There was a period of five years after each degree, that I sacrificed a lot. Dining out, partying at stylish places, vacations, travel, clothes shopping– all these things were cut to a bare minimum, or cut out altogether for significant stretches of time. Sometimes I felt discouraged, even depressed, that I was sacrificing so much without much affirmation. It was the only way I could see, though, to build an impressive body of work—and, in retrospect, the decision served me well.

Could you comment on the time after finishing school, and the importance of making?

If the art program serves its function, it begins to develop in the student an internal critique that gains breadth and richness from all the communal discourse. You ought to leave school with momentum– if you don’t, something has gone terribly wrong.

Could you comment on having a vision and what it means to be an artist?

Every vision of mine was executed rather clumsily at the start, and grew stronger through experimentation, diligent critical observation and discipline.

John Cage defined an artist as someone who is simply paying attention.

I agree with that and I would add that exciting art isn’t likely to be born of seeking comfort in one’s work. Most art is in some measure self-indulgent, but one’s process really comes to life when driven by a ravenous curiosity about one’s cultural and sensory environments.

How does one find where their work fits in the world?

That can be as much of a creative act as the making of the work. At the start, I never tried to create work for a certain type of audience or venue. I just made the work, and then tried to get it out there in as many ways as I could think of. I found a gallery quickly, but friends of mine have launched exhibition careers in shops or cafes. Almost any exposure helps: benefit auctions, postcards, and websites. There will be rejections, to be sure, from the venues you most desire–but, ultimately, if it is truly alluring work, it will find its way into the limelight.

How do you respond to interests that may only benefit you monetarily, but are not your primary pursuit?

If commerce and industry are engaged as the vibrant and ever-changing cultural contexts that they are, then one need not worry about “selling out”. Artists, particularly in academia, can be too neurotic about making money. On the other hand, if you’re selling work to people whose tastes you don’t respect, you have a problem.

What have you done to help you get where you are?

Early on, I applied to many juried shows, kept in contact with people who responded to the work, sought exposure at conferences and in magazines, and cultivated dialogue and friendships with other artists I respected.

My principal advice is: find people who are at the same level of development as you. A creative community is more likely to keep you inspired; seek out people that believe in your work, but who will also help you look at it with a critical eye.

Which do you find exerts a stronger influence on your work, success or failure?

I don’t really believe in that dichotomy. In every “successful” attempt, I see a higher potential that was not achieved. And every “failure” has ultimately yielded precious clarity. I avoid judging my work. I just methodically subject it to critical analysis, regardless of whether it is embraced or rejected by others.

What was most difficult for you when you finished school?

The period immediately after school was not a difficult one. Quite the contrary: I flourished. Having internalized the rigorous academic critique, I left feeling intellectually self-sufficient, disciplined, and clear about my priorities–and I was armed with some strong work with which to promote myself. That’s what school ought to leave you with.

A job posting says 2 years teaching experience, but you are right out of school; how do you get that experience, or should you just try for the job anyway?

I would advise young artists to seek out adjunct teaching. These opportunities rarely require much experience. I taught for four years as an adjunct, and then took the full-time job. Full-time teaching is a huge commitment, and I wouldn’t want to have taken it on any sooner. Spend some time experimenting, and building momentum in your exhibition career before you immerse yourself in full-time teaching!