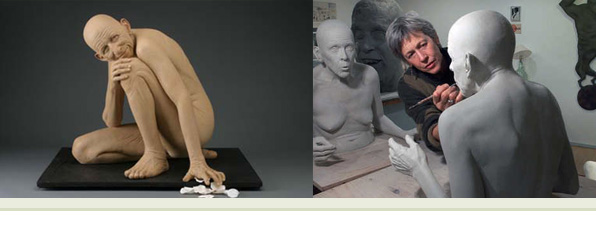

Tip Toland is a ceramic artist whose work is subtly autobiographical: within a frozen moment, teeming with humanity, exists a vessel for her thoughts and feelings. She earned her BFA in Ceramics at the University of Colorado and later received an MFA in Ceramics from Montana State University. Her previous accolades include a Visual Arts Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Artist-in-Residences in Wyoming, Oregon, Montana, and Washington, an Artist Trust GAP grant, and the Virginia A. Groot Foundation Grant among others. She is a full-time studio artist and a part-time instructor in the Seattle area. In addition, she conducts workshops across the United States. Her work has been shown in numerous galleries, including Nancy Margolis in New York City and Pacini-Lubel in Seattle. Her work is represented in both private and public collections, including the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian, Kohler Art Center, and a promised gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What was most difficult for you when you finished school?

When I finished school, I stuck around Bozeman. I was at Montana State University, and I decided to stick around because I didn’t have a plan. I had a little studio outside of the school and I could make some stuff there and sneak it into the kilns at the school. It was small enough then that nobody knew or cared since I did not have a kiln myself. I also stuck around because my sister Phoebe was at school there for another year and I wanted to be in town for her. The following year I got an artist in residency at the Contemporary Craft Gallery in Portland, Oregon. That was back when it was on Corbett Avenue, and it was this funny little three story shoebox kind of place standing up on end. I didn’t know anybody in Portland, and it was hard to go from the community in Bozeman to being all by myself. Even though they gave me a stipend and a studio to work with, it was hard and I was lonely. Other than that it was a really good opportunity to get work done. I think it’s a good thing for people getting out of school to see if they can find another community to slip into. Now, there are more things available to people coming out of undergrad or graduate programs. I was all alone at the residency and didn’t know anybody so it wasn’t the best. I was glad for it in retrospect, but during the whole thing it was hard.

Talking about how hard it was not having community, what made you choose to move here to Vaughn (Washington) and how important is the community here?

First of all, I moved to the Louisiana State University when I took a job there. As I was finishing up my one year residency at the Contemporary Craft Gallery, I said ‘what do I do now?’ so I applied at LSU for a semester replacement job. That’s what all of us had to do; we either went on a circuit looking for a sabbatical replacements or found some sort of residency. A bunch of us did that, going somewhere anyone would take us, not knowing anybody wherever we ended up. Louisiana was fabulous and thoroughly interesting. I loved it down there, sort of like another country. After that ended, I thought ‘where do I go now?’ and my boyfriend said “hey, let’s go to Seattle because I have a boat.” Back then, I wasn’t really thinking about my career. I was thinking more about ‘well, that sounds like a cool place and he’s got a boat, yeah the ocean!’ I said why not! I just wasn’t really focused on my career, I was more focused on having a good life instead of having a career. I decided to come with him to Seattle and I’m really glad that I did actually. I kind of feel like there have been angels watching over me the whole way and pointing me toward Seattle saying “go there go there go there.” I got to Seattle and immediately got involved with Pottery Northwest because I had to find a place to work since I had no kiln and nothing set up. They took me in right away at Pottery Northwest just because they are kind and because my father’s best friend introduced me and knew Jean Griffith, who ran the place. Jean took me under her wing and I taught there and worked there. I had this immediate community and I met all these clay people from there. I had been in Seattle since August 1984 I’ve only been down here in Vaughn for the past 11 years. At that point, I met my husband and we just had to get out of Seattle. There is just too much traffic and he was a bonsai guy and needed some acreage and we both needed some peace and quiet. By then I was pretty established in Seattle, so I still teach in Seattle. I commute there twice a week to teach and the rest of the time I’m a studio sculptor here. I get the peace I want while still having that big city community, which I am grateful for and always want to keep that alive by staying in touch with the University and the crowd of clay people that are out here.

What type of boat was it that he had?

A rowboat! It sucked! He kept saying how he lived on it and all that. It had a mast on it, but it was still only like 11 feet long and very little.

So you’re saying at that time, your professional goals were not at the forefront; it was more about being happy. What where the professionals goal that you did have after finishing school and have you achieved them?

I have always pursued my career, even though I say that I wanted to be happy, I have always been making some kind of art. It hasn’t always been clay, but there’s always been an aspect of clay that’s been in the work. Ever since graduate school that’s been on the back burner; my interest in furthering my career. When I got to Seattle, I wanted to get affiliated with the gallery and I knew that if you wanted to get affiliated with the gallery I had to make the work. William Traver was interested and said “come back to me in six months and show me what you have.” Then I was in a little Jackson Street Gallery and all these things were good, they were a little stepping stones. Finally, Bill Traver said “we want to give you a one-woman show, sign here & here.” Once you start down that path and you know you want a gallery to represent you then you have to make the work so that you can have new things to show the galleries. Once you’ve signed up with a gallery then you have shows and then they want to have new work. You have a contract and you are committed. It’s been like that ever since for me. For some reason I keep signing up for these shows and I have to do the work! Sometimes, I’m like ‘wait a minute, will I ever get a break?’ but that’s how it goes. It’s just like that. Once you put the whole engine in motion, it has a life of its own.

What do you find influences your work more success or failure?

No one’s ever asked me that question. That’s a great question, because failure makes me mad and rejection makes me mad. No one is ever just given the green light. Or maybe some people are. It seems to me that everybody gets a rejection letter from some show or definitely from grants, you’ll definitely get rejection letters for grants. Being passed over always makes me mad, which instills in me that feeling of ‘I’ll show them that I’ll make that best god damn work that they ever saw!’ and they will be like, “why didn’t we give the money to her!?” I have to say when I’ve been given a break it’s just been incredible to me, it has just lit a fire under me like nothing else. The first big break was being able to show with William Traver in Seattle. The next big break was when Nancy Margolis was interested in my work and she was in New York City. This was just when Kenny and I got married and I said ‘honey, can you hold down the fort so that I don’t have to teach so much so that I can get the work made? This could be my big make it or break it moment so if I can give her a nice show this will really make a difference.’ So, he said “yeah, of course I’ll do that for you.” So I gave her a nice show and it probably didn’t make any difference at all. Then when Barry Friedman said “I want to show your work,” it was like this chance. When you are given a chance, I think of that as enormous success or the universe saying “what do you have up your sleeve? Can you do it?” So when I’m given these chances, I just give it 110% and that’s really what brings the best out in me. Success really lights a fire under me.

You mentioned a bit about Kenny being your husband and how he helped you. I wanted to ask about balance in your life. It sounds like he helps with that balance, but what other things contribute to balance between home and studio life? How do you get it all done?

First off, I don’t get it all done. I absolutely don’t. Kenny is the reason that I don’t have to work a full-time job. I got married later, when I was 49, so I was used to supporting myself until then. I was renting places and was a struggling artist. I didn’t sell enough to make it and occasionally I would get a grant. As an artist, you will have a big chunks of money come your way all at once, then you have to make that last for years. Then you get these little teaching gigs, but it’s not very much and you run out of money. You’re completely out but somehow the universe has always put something in my path where I could either teach or apply for a residency or have a show where I could sell something and have a little money. Then I met Kenny and he had a real job! He had a regular job and he had his shirts cleaned. I never ever was with a guy who had shirts that were actually dry cleaned before Kenny. I was just writing somebody this morning how I have no balance in my life. My life feels like it’s all studio time and there’s no time for hardly anything else when you sign up for a show. I had a show with Barry Friedman last March and my father died two weeks before that and my mother wanted to have the memorial service a week ahead of when the work was going to be picked up from the studio and I just said ‘no mom, I can’t. Dad’s dead.’ I don’t mean to get morose, but I felt like I couldn’t even take time for my dad’s funeral and that made me so mad. What if life asks something of you and you have a show? The show must go on. I suppose there are situations where they would postpone a show, but not in this case. They had done all the news releases, so I had to have the work be available for pickup that one week after the memorial service. I had to go back to Philadelphia and it was a terrific stress but It’s always like that. Thank god things like that don’t happen all the time before a show because I never feel I can do justice to my friendships or relationships. My health and everything else gets put on the back burner and the show must go on. It’s just flat out fear and loathing to get the work out the door then. Some people like Phoebe can get their work done two weeks ahead of time and have it be just free sailing. I’m more like Dick, where I’m fanning the paint to dry as it goes in the door to the gallery. [laughs] Maybe not quite like that. For me, it feels very black and white. I either have a show and it’s just full tilt or I don’t have a show and then it’s like I have all this time. I feel that’s very useful for a certain amount of time and then it feels like I’m not doing what I’m supposed to be doing, I’m supposed to be making art, so I can’t have too much time off. It’s black-and-white. I haven’t really hit a good balance, but I’m getting better. Now I break every night and I don’t stay up all night. I can’t do it anymore, and I go to bed now by midnight and then I get up and do it again. So I have better balance, but it’s still very rough. That’s a hard one to strike the balance.

Does having animals help you keep a balance?

Yes it does. Every morning, first thing, I walk the dogs and it gets me out of the house and gets me moving and saying ‘oh, it’s pretty outside.’ There is a whole gang of women I walk with and they all have dogs, so we’re like this big troop going down the road and that’s nice.

When you exhibit your work, how do you know what venues are right for you and how do you find them?

I think it’s really good to put your work in a gallery so you can get into this group, this stable of artists even if they’re a little better. It’s good to have associations with people who are as good or little bit better. I think that’s always good, because galleries also want you. They want up-and-coming, rising, new, exciting, potentially cool, great artists. They’re interested and they want to be the one to discover you. You have to do a little hunting for galleries and if you can, talk to other artists that are showing with this gallery. Find out what is this gallery like, do they have integrity? Is there anything that you can sign so you know you have a clear contract? How often can they show your work and who is on their roster of collectors, not that you would know any of them. If they are selling this person’s work, then most likely they would be selling my work because I am enough like them. Also, get someone who’s a little more seasoned as an artist then you; for me, it’s been Richard Notkin. He’s a little older and shown much more. He’s been able to counsel me on “this is what price your work should be” because I didn’t know anything. Its very good to have a mentor, to find somebody you trust somebody who’s been through from A all the way up to find out how the pricing goes because that’s a very important thing. By finding galleries, you want to be putting yourself in a good position if you can. Not only to be seen, but to be recognized; to have your name be recognized by the community or by collectors. People say, “oh yes, you show with so-and-so. They’re a nice guy” or “thats a nice gallery”, that sort of thing. I think it’s good if you feel really supported by a gallery; not just financially, but emotionally. They actually like your work and they want to support you as an artist. They dig you and they want your work and they like your work. Thank god I’m in a gallery that seems to like my work because I don’t think I could take it if it was just the money end of it. I’m just so grateful to them. At first you’re hunting down galleries you just want to get your work up and have it be seen so you can get something on your resume. I would show in nice coffee houses. I would absolutely take all kinds of advantage of all sorts of places. Look for good shows where you know that they’ll have some exposure maybe even a catalogue will be made. Before you get in a gallery get into some good shows that you think will further your name being recognized and your work being recognized. That’s what I did basically and it was a very helpful thing.

How did you find your mentor Richard Notkin?

He was my teacher when he was a visiting artist at Montana State University during my last year there. Michael Peed was on sabbatical and Richard came and we were just similar, cut from the same cloth in many ways. I respected him so much and he seemed to like me too. He was just very accessible and available. I could ask him a lot of questions and then he went and married my sister Phoebe and so now he has to answer my questions! So thank god for Dick Notkin. If you had anybody looking out for you like Dick does for me, god bless them. Dick goes to so many workshops and so many residencies. He’s such an internationally known guy that he could open a door for you here and there and he has for me. He honestly feels he wants to support me, and not just because he’s married to my sister.

Do you think that there are certain privileges or disadvantages that today’s ceramic artists may have that did not exist years ago?

When I graduated, there was no preparation at all for being a professional artist covered in school whatsoever. There was no interviews like this, there was no mentor. You were just expected to somehow know what to do. My slides were just abominable, putting an egg for scale in every one of my pictures. I had no idea about photography. I came out knowing nothing, so I have to say I wasn’t at all prepared and I had to scramble. I would ask ‘what are you supposed to do? How are you supposed to do that?’ I was an ignoramus. I think now people are way more prepared to get into being professionals. They know what’s needed and know about options. There are more options in terms of residencies like Penland, Haystack, Arrowmont and all kinds of places where you can go after school to just chill a little bit but still be able to do your work and think about what the next step is. You can get a bigger picture of what’s out there and think about it and so there are many more opportunities like that. I think there’s just more literature in terms of news and availability of what is out there. I just didn’t know a single thing. No, I knew one thing. This contemporary craft gallery that I applied for; somebody said that you should apply for that, so I just did it. I didn’t know of any other one except for that. I think there are lots more possibilities for people now. Yet now it’s harder because there are a lot more people in the ceramic world. There are just so many more people and they’re good. I just went to my nephew’s BFA show and he’s doing things that make me want to fall to the ground and I’m just so humbled at how professional his work is at a BFA level. He’ll have no trouble getting into graduate school. I can’t even imagine what he will do for an MFA thesis. When I got out of my bachelor’s of fine art, I applied to graduate school with ashtrays and vases and I didn’t do anything like what I am doing today. I never did anything like that and I was accepted, so I was thinking ‘they accepted me? Boy, the competition must be bad if they accepted me on the merits of ashtrays that I had made while I was in Wyoming’. Today, you have to be better. You need to be good right off the bat because the competition is stiff so you have to be serious earlier. People coming out of school now have the access to knowing all kinds of other artists, have the ability to see their work online. When I was getting out of school, computers where not part of everyday. Nobody had their own personal computer, so the only way we could find out about what other artists were doing was through periodicals. I studied them a lot going through them like crazy but still there’s no way to compare to today. Nobody had a website. It was just a different world and now people out of bachelors have their own website. They can make it overnight. It’s terrific in a way because you can get a million people seeing your work and that’s terrific. It is also way more competitive because of that. So it’s yes and no. It’s good, it’s bad.

What in your opinion are the greatest challenges facing students who are about to enter the field professionally?

I don’t know if this is true, but there might be more pressure to have cohesion in your work so that you would present a body of work to a gallery or residency or grant or whatever. There might be more pressure to have a cohesive body of work, which takes away a lot of freedom in a way for experimentation. That, I think could be the biggest and maybe the saddest outcome because there’s so much need for recognition and a tendency to get a look, your look for your work, and have a line whether its pottery or whether it’s your trademark look. I sometimes feel sad about that. I was told when I was graduating that my thesis show couldn’t just be this and that; it had to be really cohesive, had to look like it came from one hand. It irritated me when they told me that and I thought, ‘what’s graduate school for if not to be really experimental?’ I was very idealistic. I just kept thinking it’s still so important to be really experimental, but that’s not what they wanted to hear and I think now it’s even harder. Beyond that, there’s more competition. I think there’s a lot of pressure; like when I taught at the University of Washington, there was a lot of pressure and faculty can have an enormous influence. That is a good thing and that is a bad thing. It’s a double-edged sword, I think. Depending on who they are, you adore your faculty. Especially if they’re behind you supporting you, but there is also some quiet pressure to keep on doing what you’re doing. A faculty that doesn’t like your work that’s always going ‘what are you doing that stuff for?’ then you tend to mistrust yourself and second-guess all your intuitive feeling. Also, because you’re graduating, you have to justify and defend. All of your ideas have to be defendable and, in a way, you can’t afford to just go on a hunch or say ‘I was following my hunch and it just felt right.’ So you don’t exactly get a chance to do that until you’re out of school. I really support people trying to forget everything like that and go through school and totally take all the good stuff and then go ‘alright, what do I truly want to do? What’s authentic to me?’ Its like a discovery, like mining, trying to find your voice going deeper and deeper into layer after layer going down and to say ‘this feels very integral to me, this is really me.’ That’s the whole job of an artist, to get down in there. School is so useful and can also be such an obstacle to that. I’m giving you one hand and the other for all the questions. That’s what I see from my perspective because I remember being at the University of Washington, teaching for a semester and one of these kids is making the most ridiculous work frankly I kept saying ‘honey, what has this got to do with you? why is this important for you to make this work?’ That is the $64,000 question, why is it important for you to make this work? That can be completely blindsided in school and in a way, it’s a whole lifetime of working to get to that place once you feel you are really on the right track and you’re being really true to yourself that’s what I think it’s about. That’s the biggest challenge because even without school or without any influences one way or the other, it’s still so cloudy you can’t tell. You don’t know. It’s hard as a teacher to lead somebody if they just don’t know. It’s also like being a psychologist trying to get somebody to say what feels good for your fingers. Forget your head, what does your body feel like doing with the clay, trust that. It’s actually a good idea if you don’t think about it too much.

Is there any other advice you would offer to an emerging artist?

It’s true that many people who will come out of graduate school won’t continue on, and that’s fine. That’s okay, but it takes a great deal of tenacity to hang in for a lifetime of doing it. I think you have to have a big ego. You have to have a sense of ‘I can’t not do this.’ I heard this one guy, I don’t know who it was. He was some famous actor, and his son wanted to be a famous actor and the father said ‘I did everything in my power to talk my son out of it and if I couldn’t talk him out of it then I gave him my blessing.’ You have to really have it in you, it has to be your destiny to do it . I could call it dharma, but sometimes that’s a funny word. You feel like “I have to do this stuff, I don’t know why but I have to do it I’m just born to make stuff.” I don’t always know what, but I have to make stuff. Everybody, no matter who you are, will make colossal failures. So not to worry. It actually is a good thing if you make a lot of colossal, miserable, embarrassing failures. Do not be afraid to make big, enormous failures because that says you are actually trying new stuff, you’re exploring new territory. Then it also says that if you don’t have the failures, you won’t recognize the good stuff. It’s not human to make success after success. You can’t help but make miserable failures, but it’s easier to see the difference between a failure and a success and say “oh, this is much better than that.” Call in people from time to time who you trust their take. People who you really, really feel like they get you and can see your work and help speak to it. It’s going to be like this voyage, you’re going to be in the fog sometimes. But anyways, it’s just terrifically interesting to be an artist because you never really know. That’s the way it should be; you shouldn’t know ahead of time, you should be discovering who you are throughout like “oh, I didn’t know that was coming out of me.” If you start to feel like you know ahead of time, you’re not taking enough risks. Keep being surprised by yourself.