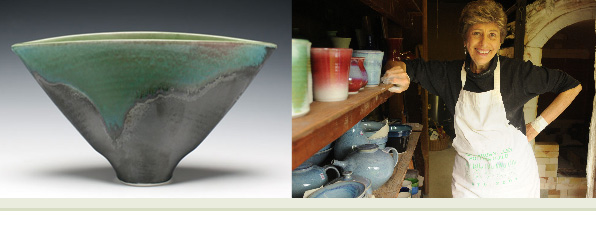

Angela Fina graduated from the School for American Crafts at RIT in 1965. She has taught at Nazarath, Sheridan College in Tornato and RIT, taught at Penland,Scripts College and in Italy. and in 1979 she moved to Amherst Massachuttes and became a full time studio potter. Angela passed away in November 2013 and she is missed.

I, and many other older potters, would love to see young potters get into the business of full time potting and making a living, though we see how difficult it is. There is a myth that it used to be a lot easier, but don’t bother thinking that…it has always been a difficult row to hoe. The big problem, of course, is money…having enough to get started with equipment, a stable studio space, enough to give you time to figure out your market and get established, and enough for a rainy day fund to carry you over when things go bust.

Another big problem is finding a commercially viable line of work that you feel has integrity, as well as popular appeal. It has to be something that is reliable to make (i.e. not a fussy glaze that only turns out occasionally), that you can make a lot of without going nuts and that you can sell at a price where you are actually making more than minimum wage after you subtract all your expenses.

Probably the only reasons I’ve been able to do this are: 1. The business course I took before I quit my teaching job; 2. The fact that I didn’t try to do it alone until I was 40, and had saved enough to solve the first problems: money, studio, and time; and 3. The fact that I was willing to change my work in response to the market.

I think of myself as a commercial artist…if it doesn’t sell, I don’t make it again. This has led me away from my “heart and soul” pots, because only other potters liked those. There was an article in the last issue of Studio Potter magazine on sources of income for potters. Another survey was done by Wendy Rosen, who runs the biggest national wholesale craft show in the country, which showed that 80% of crafts people are subsidized and don’t actually make enough to live on. Many of these folks can make their heart and soul work and sit around till someone buys it…or not. But the 20% of us without alimony, a trust fund, or a spouse with a real job, have to face the reality of bringing in a certain amount of money every month, year after year. This means finding a large market and making work for that market. I know this sounds horrible to students, but it isn’t. It’s another facet of creativity…designing for the public…the part of the public who are interested in owning hand made pots.

The skill you need more than any is the discipline to make your pot making your job by putting in the hours each day as though you were working for someone else. You organize your schedule so that you ship out work to galleries on time. You plan for the events you will need to sell enough: studio sales, craft fairs, wholesale shows, specialty markets. You need business skills to price your pots correctly, to collect the money owed you, to keep records so you can analyze your business. And you need to stay flexible in what you make so that you can go back to designing a new line when your work stops selling. I’ve never stopped making anything that was selling well, even when I was getting tired of it myself.

Of course there are other ways to be able to be an artist when you leave school. I have a painter friend who runs a house cleaning business 4 days a week and she paints the other 3 with no need to paint “commercial art.” A sculptor friend is a Teamster truck driver and gets health insurance, sick pay, and vacations, and making sculpture with a free mind. And of course, if you can find it, there is teaching: K through 12, prep school or college. A writer friend of mine became an electrician so that he could make a lot per hour and thus have more time to write.

The entire art of ceramics involves compromise: from the clay body you use to the kind of kiln, studio space, to the technical feasibility of making what you imagine in your head. The life of being an artist will involve a lot of compromise, too. Your passion for being an artist will be tested all the time. It involves choices everyday: how you spend this hour, what you spend your money on, let alone what you make. Many artists have had to drop out because of life events, but have then come back. Some have had to accept the fact that their art time will always be very limited and fragmented. But the question is: how important is being an artist to you? Are you willing to find a way even if it’s not the ideal you wish you had?